|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

South Africa’s wine industry, like the country itself, is fascinating and complex. South Africa is distinctive for being the oldest of the New World wine regions, yet the regulations, restrictions and lingering stigmas of apartheid have made South Africa appear relatively new in the minds of many American wine lovers.

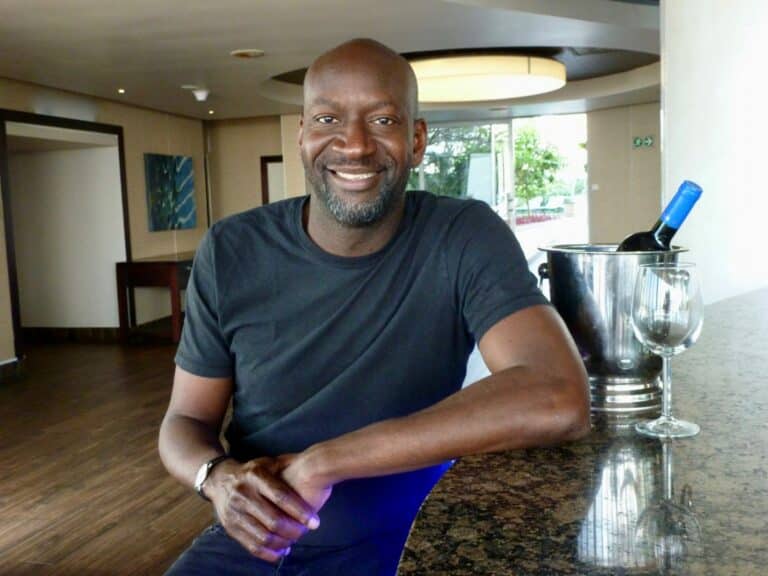

South African native, Jabulani Ntshangase (pronounced most closely to “chun-GAH-say”), took an interest in wine that began in the United States back to his home to become South Africa’s first Black winery owner.

His passion for the wine industry led him to create a program at the esteemed Stellenbosch University specifically designed to attract and education black students to be winegrape growers, winemakers and winery owners. The legacy of this program has, in many ways, made Ntshangase the father of the black wine industry in South Africa.

Jabulani Ntshangase’s Humble Beginnings in Wine

For such an accomplished man, Ntshangase’s entrance into the wine would be surprisingly unglamorous, beginning as a stock clerk for a New York wine shop. His education in business administration had taken him to the United States on a United Nations scholarship and although he was a teetotaler, he needed a paycheck.

The next steps were slow ones and his history of abstinence from alcohol meant he ventured into wine cautiously and studiously. His first education in wine was actually listening to what others said about the tastes and smells. He learned to look at it and to smell it long before he wanted to taste it and appreciate wine in the way many wine lovers do.

From a business perspective, however, he realized that there was potential. “This was the late 1970s and Americans had not quite acquired a love of wine,” he says. “There was no Wine Spectator, no Robert Parker or Wine Advocate.” He stayed at the shop for twelve years.

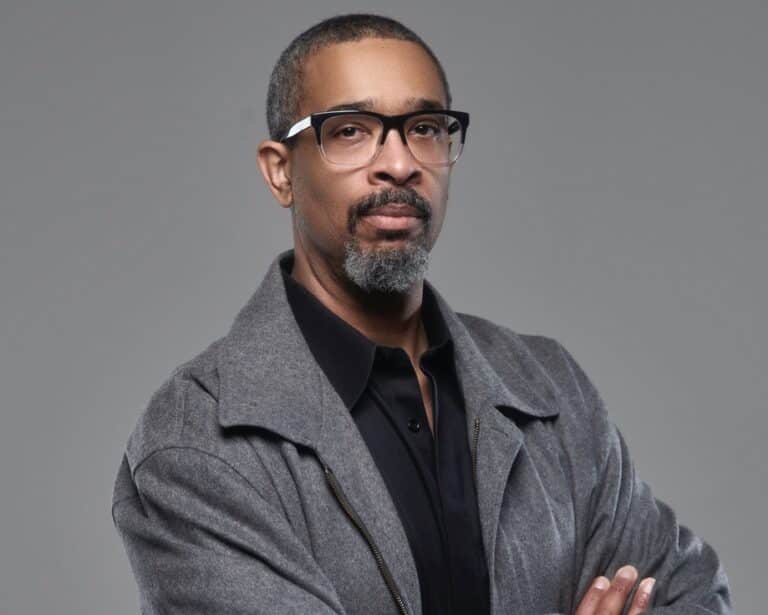

- Akin Omotoso Blends Race, Gender and South Africa in Colour of Wine

- Ntsiki Biyela Uncorked: South Africa’s First Black Female Winemaker Delivers

Bringing South Africa to the United States

By this point, there was something else happening in the world. South Africa’s practice of apartheid was finally coming to an end and Ntshangase returned to his home country in 1991 as sanctions were being lifted and apartheid was being abolished. Ntshangase knew that South Africa produced a lot of wine, but because of apartheid sanctions, people in the United States were largely unfamiliar with wine from his country.

He used his knowledge and connections in New York to begin importing South African wine into the United States, a lucrative business that put him directly in touch with the winemakers of South Africa who wanted to export their product to the United States.

“Americans were skeptical,” he recalls and they had questions. “Had the heart of the apartheid people changed?” Although there was a curiosity about South African wines, it was not an easy sell initially.

“It was difficult to make people believe that South Africa had changed,” says Ntshangase. But the suspicions of South Africa were only temporary and not only were people interested in the wine, they were interested in him and the involvement of black South Africans in wine. “People loved the wine, but always asked if there were any black winemakers.” In light of the recent ending of apartheid, it seemed a natural inquiry.

Growing the Future of South African Wine

Ntshangase’s entrepreneurial mind decided to push the boundaries and he made a drastic decision in 1995 to do something revolutionary in South Africa that involved the country’s youth.

At this stage, Ntshangase did not set out to make wine directly, he wanted to influence who would be making the wine, growing the grapes and owning the wineries. He took his passion for wine to 14, 15 and 16-year-olds in high school. It was a bold and insightful step.

“There was a profession out there that their parents and high school principals didn’t know about and didn’t communicate to them; degrees in viticulture and enology none of them knew existed.” Ntshangase planted the seed in the minds of young people that wine was an industry that they could take ownership in.

Inspiring youth was taken full circle when Ntshangase established a program with Stellenbosch University which has a viticulture and oenology program and is over 125 years old.

This program, still thriving today, has produced some of South Africa’s top black winery owners, winemakers and vineyard scientists. “It’s my social responsibility,” he says of the program at Stellenbosch and over the years, more than fifty students have graduated and are now employed in various aspects of the wine industry.

That would be legacy alone, but Ntshangase also became the country’s first black winery owner as one of the partners that established Spice Route Winery and Vineyard in 1998. Selling his interest after two years, he then went on to found Thabani Wines and his newest project, Highberry Wines, named for the high elevation of the vineyards in the Stellenbosch region.

If you want to taste some of Ntshangase’s wines, look for the Highberry label. The 2014 Sauvignon is described by Ntshangase as “very fresh with some lovely minerality. Gooseberry, green apples…almost like a granny smith nuance. Yet so flavorful you don’t even feel the acid.”

He says that it leans more towards a Loire Valley expression of the grape rather than New Zealand. Ntshangase says that this is a signature of South African wines. Being the oldest of the New World wine countries, the wines lean towards a classic, European style, but with a hint of New World flair.

RELATED: 6 Tips for Serving and Storing Wine

Highberry is just getting started, but this fall, look for the 2014 Highberry cabernet sauvignon to be released and Ntshangase says that a Rhône blend of syrah, mourvèdre, and cinsaut is on the way for the future. (The Thabani label will release its next wine in 2016.)

Ntshangase will always own a winery, but his vision is much broader than that. “What’s always in the back of my mind is to grow and grow more. Not just the grapes, but growing the number of consumers.”

He means Black wine consumers in addition to wine consumers in general. “The only method that works is if you involve the people. Not just in part of the work, not just as participants, but as the owners and growers.”

Black South Africans have worked the vineyards since grapes were planted in South Africa, even through apartheid. But Ntshangase’s experience with all levels of the industry is what drives him to continue to expose blacks to the wine industry.

“You’ve had our people in there using their hands, but it would be great to use their minds as well. Definitely as great pickers [of grapes], but you also want people that will be thinking of style. Not just varietal, but also in terms of [things like], ‘should it be fruitier,’ ‘should it have oak’, what is the American consumer wanting?’ We want people to go that far, to have global insight.”

This is how he wants the students he sends to Stellenbosch to think and indeed the populations of South Africa.

To learn more about Ntshangase and Highberry Wines, visit his site.