|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“If you can raise enough to have some to give away, you’ll always have enough for yourself.”

“The first time I got hooked on farming, I was six years old,” Elisha Barnes says. “I had just gotten off the school bus, and my father, who was out in the field breaking corn with my uncle, climbed on top of our old tractor so I could see him and called my name. I walked over, and he put me on the tractor and explained how to drive it.”

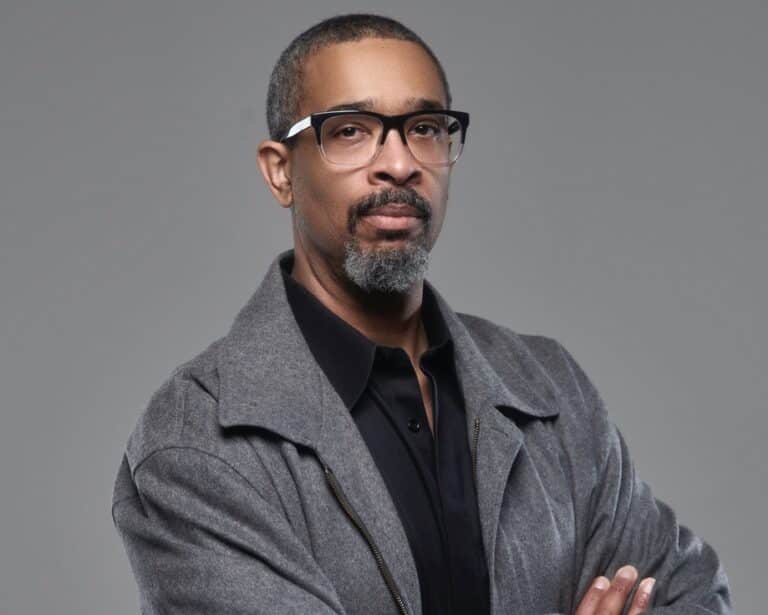

Elisha Barnes, a pastor, peanut farmer and owner of Pop Son Farm, was born and raised in Southampton County, Virginia. Specifically, he is a fourth-generation peanut farmer, so hearing that calling at such a young age makes sense. It’s in his roots.

Black Farmers and U.S. History

Barnes passionately works in an industry that has seen a sharp decline concerning the Black community. According to the U.S Department of Agriculture, Black farmers only account for 1.3% of the US farming community, down considerably from 14% in the 1920s.

One primary reason for this decline is that many Black farmers have had their land stolen, typically through force and violence. In addition, discriminatory federal policies and financial lending practices also come into play, as Black farmers were often denied access to USDA programs managed by locally elected boards.

Barnes and his family are some of the few who could preserve and were very fortunate not to experience what other Black farmers did. “Southampton County, at the turn of the century, was primarily Black-owned,” he says. “It was considered a wasteland until the value of peanuts came in.”

It Begins with Family

Barnes comes from a large family, with six brothers and sisters raised by his parents. “My parents were always together,” he says. “We were raised with my mom and dad, every single day teaching us and preparing for us. We were poor but didn’t know it because we had love and the necessities.”

As he continued to describe his childhood, it was clear that Barnes was raised in an exceptionally loving, compassionate home. “It was a joy,” he says. “I look at my family now and wonder how anyone can exist without that positive influence. My father and mother made sure that we were well taken care of.

I appreciate who they were. They stood shoulder to shoulder. All those years growing up, I never heard my parents argue. If they had a discussion, they’d go to their room and close the door. You’d hear a light little rumble, but that was it. They’d come out together, never glaring at each other or anything like that. We had parents that wanted to love and teach love.”

His parents’ teachings also extended to farming. “One of the things my father taught me is if you work, work well, be honest and treat your land well, if you do your part, the land will do its part,” Barnes says.

“Peanuts taught us work ethic. It taught us sitting at the house looking at cartoons won’t get you anywhere. People call us workaholics, but we know what we want out of life.”

Early Years

Barnes says that he knows his family acquired the farm sometime before World War II, but the records are cloudy at best. “My father was drafted into the army, so he put the farm in my grandmother’s name in case he didn’t make it. He sent money back while he was away and finally got the farm paid for. It’s hard because all of the people who would have known these details are gone now. He purchased the farm, but we were sharecropping the land we lived on, which was owned by a peanut company.”

After the war ended, Barnes’ father came back and raised his family alongside his wife. Barnes says that his family’s farm comfortably sustained his large family. “We raised everything we ate: cows, hogs, chickens, ducks, turkeys, etc. That’s where we got our protein,” he says.

“Once in a while, we’d get to go fishing. What we ate, we raised. We ate lots of fresh vegetables. When I was 12 years old, I took a liking to hunting—killing deer, squirrels and rabbits. I started putting food on the table. We never in my entire life had a day of hunger. We always had an abundance. Mom and pop made sure we had plenty, though we may not have had what we wanted.”

It’s evident that the farm and his parents profoundly affected Barnes and shaped him into the person he is today. He speaks highly and lovingly about his parents, especially his father.

“We [Barnes and his siblings] know the drive my father had. He would get up and go to that field and work from sun up to sundown. I thought he was ten feet tall.” However, reality checked Barnes one day when he realized he had grown taller than his father.

“I literally cried,” he says. “I saw him as a giant of a man, and all of a sudden, I was looking down at my father’s head. He taught us how to treat people and how to be honest. He taught us integrity. He taught us how to go out and earn an honest day’s living, expecting nothing but an opportunity. He taught us to make good on every opportunity that we were given. And we did that.”

Barnes says his father was a big and strong, gentle giant who didn’t let anything bother him. “To get him riled up, you had to really work. If you ever got him on that side, you best be making tracks. I only saw him that way once. Luckily the guy he was mad at was faster than him. “

As for his mother? “My mom would fix breakfast and call everyone to the house to eat. My mom would make sure we still studied. Mother was feisty. She said, ‘You go out there, and you do your best, but don’t let anybody beat up on you. Stand your ground if you know you’re right.’”

- Jim Adams Farm & Table: Honoring a Multi-Generational Farming Family

- Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones Embraces Uncertainty in Farming and Beyond

His parents instilled an impressive work ethic in Barnes and respect for nature and the circle of life, which is why he loves being a farmer.

“The fact that I get up in the morning,” he says, “And actually know I am affecting my livelihood and that I’m close to nature. I get to influence the farming process from start to finish. You don’t have to rely on someone to create something. Laboring with your hands and watching the rewards, it is nothing less than a miracle and nothing less than fantastic.”

Education and Career

Barnes mentioned he was formally educated, but the surprise is that he has an automotive and diesel mechanic degree from Nashville Auto and Diesel School in Nashville, Tennessee.

“I never had any formal schooling for agriculture, he says. “The schooling helped with the repair and management of our equipment. In high school, I took woodworking, welding and shop. I have a welding degree too. I wear a lot of hats.”

Barnes’ motivations were preparing for the future, and he said out of all of his siblings, he was the only one who had “the mind for farming.” His brothers and sisters graduated from Hampton University, Virginia State University and Norfolk State.

“My father was a sharecropper who owned nothing but was able to put all of us through college,” Barnes says. “He said everyone in our house was going to school.” Like many sharecroppers in his day, Barnes shares that his father had to stay home and work the field.

“He was limited in his life due to his limited education. He only went as far as fifth grade…so he was determined to give everyone an education better than he had. And we did.”

Barnes graduated in 1976 and got a job at International Paper Company, working there for 30 years. He married, and by 1989, he had saved up enough money to buy a 64 ½ acre farm. He also kept it real with his wife and let it be known early in their marriage that farming was in his blood, and his goal was to own a farm one day. Her response? “I don’t know anything about farming. I’m not milking the cows, but I’ll go with you wherever you go.”

Barnes says he searched for two and a half years for a farm. “Many people were not open to selling to me,” he says, “But I was blessed to have a real estate agent who stuck with me through that process.” His real estate agent kept her ear to the ground and found the perfect property for Barnes. “I signed the contract that night.”

“The next day, I found out in the papers there were three or four backout contracts. It was a God-ordained thing that I was able to obtain it.”

For decades, Barnes maintained his career and farm, working eight to ten hours at the paper company, then going home and working in the field, sometimes for four or five hours a night. “You do anything for what you love,” he says.

“It doesn’t matter what your work schedule is; you’ll make time for your passion. In 2019, a fantastic event occurred; the farm across the street from where he and his siblings were raised, which belonged to his father, went for sale. “My oldest brother and I were blessed to be able to buy it back.”

As mentioned before, Barnes’ father put the farm in his grandmother’s name when he left to fight in World War II. But after his grandmother died, he says the farm “got out of our hands somehow.” So, Barnes wasted no time getting it back up and running. “I was able to raise peanuts on that farm in 2021, and it produced a wonderful harvest this year.”

Considering he was farming peanuts, one would assume that they must be easier to manage. “I wouldn’t say they are easier,” Barnes says. He explains that peanuts are “sun-cured,” which is a slow process that makes them so sweet and tasty.

“I give people this comparison. If you want a raisin, you can’t put a grape in the oven and expect it to be a raisin; that will destroy it. But if you allow that grape to slowly cure, it will turn into a raisin. Peanuts are the same way. A lot of what you do determines the flavor of the end product.”

Peanuts are a lucrative business. “Everything else was fine, but peanuts were the money crop. That’s what drove farms to be bought and sold. That is the history of the county I live in. Suffolk was known as the peanut capital of the world at one point.”

Currently, there are four types of U.S. peanuts. What sets the Virginian-style peanuts apart from the others?

“The Virginia Runner type is larger and sweeter,” Barnes explains. “They are world-renowned for their flavoring and oil. Up in Wakefield, they prided themselves on having world-famous Virginia hams. Allegedly, the hams tasted so good because they ate the peanuts their farmers let them graze.”

Modern Day Farming and Sustainability

A new focus on sustainability and farming has gained popularity over the last few years, especially in the Black community. Four hundred twenty-one colleges and universities offer sustainability programs for bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees.

There has been an uptick of Black millennials, and the community has embraced sustainability not only in rural areas but also in city life. When asked about his thoughts about this, Barnes says he loved it.

“It connects us to history. One of the things I’m passionate about is a saying I heard from my high school English teacher, ‘Any nation or people who forget their past are doomed to repeat the mistakes of their past.’ Farming is a passion. I look at farming as an art because I’ve seen the blood, sweat and tears that go into working the land.”

Barnes says that land is not made, meaning it doesn’t grow and can’t be replenished, and if someone isn’t a part of creating basic needs, they’re at the will and mercy of the powers that be.

“I know I won’t go hungry as long as I am physically able. I have deer, rabbits and squirrels. People say ‘ew,’ but I was encouraged to think of food that way. If Millennials get back to land, to what lets us control our destiny, if they get back to the idea that, ‘I can put my hands in this and see the reward on another end,’ we’d see more sustainable efforts in the next generation.”

However, for some who grew up strictly in the suburbs and urban areas, does Barnes honestly think that sustainability works there just as well as in rural places? “I do, I really do. I know farmers who have come out of the city and bought a piece of land. There was this one gentleman I know, he was introduced to farming in school, and it tickles him to death to be a farmer now. I wish that was a legacy that had honor in people’s eyes rather than disdain.”

The gentlemen that Barnes mentions isn’t the only one giving up a fast-paced life for environmental work. There have been multiple reports of people, especially engineers, who have left the corporate world for farming in recent years. Barnes welcomes them in, saying they bring in a new, fresh perspective since they’re knowledgeable in other fields.

RELATED: Somali-Born Visionary Leads Food and Economic Sovereignty in Maine

“No offense to anyone, but farming is so much more than sitting in a cubicle. Farming allows you to get back to the land and have a productive and positive life. All of my siblings have desk jobs, and that’s good, but my passion is planted in this dirt. My father used to say, “If you’re doing what you love, you’re not working; you’re just enjoying living.”

However, he stresses that it’s not easy and there’s a learning curve, although in some ways, farming is easier because of technological advancements. “With new technology, we don’t have to inhale dust from the field,” he says.

“We used to rely on wind direction to keep the dust out of our faces. Nowadays, technology can practically harvest the crops themselves. I even witnessed a farmer reading a book while GPS controlled his tractor up and down the field.”

There are some challenges, such as chemicals and the diseases that come as a result. “If you don’t put down the chemical, your crop is going to be limited. Now, there are diseases I’ve never heard of as a boy. Leaf Spot was the only one I knew growing up. Ironically, these new diseases come out of chemicals in the soil.”

Barnes also points out how climate change has produced some challenges. “I wish we could get back to simple life,” he says. “Weather patterns have changed, and we need to adapt to understand it. Growing up, we had real snow; now we just get a dusting.”

But Barnes is still holding on to optimism. “It is an honor to work the land and let the land supply for you,” he says. “Agricultural programs now teach crop rotation, soil samples, how certain crops don’t grow in certain areas, etc.

North Carolina State invited me to a sweet potato conference. I went, and they were experimenting with Covington Sweet Potatoes, which I had been planting for a long time, instead of the typical Beauregard. It means so much to me that they are bringing in agricultural communities that way and connecting students with people who are out in the field.”

Perseverance and the Future of Pop Son Farm

When the world collapsed in 2020, Barnes, like everyone, felt the impact of COVID. Barnes says he was concerned and took it seriously, especially after almost losing his brother to the virus.

Barnes says his faith gave him strength despite the obstacles, which he passed to his congregation. “I said that God has given us this opportunity to do the best we can for ourselves.” Barnes says he raised a lot of food and gave it to those struggling in the church and the community. “I gave away four pickup truck loads of sweet corn last year. I’d rather give it away than have it rot in the field.”

RELATED: African American Organic Farms Become the Focus of Philanthropic Tour

It’s easy to see his parents’ influence in Barnes’ actions, especially manual labor. “Laboring with your hands and watching the rewards, it is nothing less than a miracle and nothing less than fantastic. I tell people I am living my best life right now at 66 because I get to do what I love. It has finally become financially beneficial to me.”

Indeed, Barnes is partnered with Hubbard Peanut Company (also known as Hubs), owned by the Hubbard family, Virginia’s oldest continuously family-owned and operated peanut processor since 1954. Marshall Rabil, the grandson of the Hubs founders, wanted to launch a single-origin peanut product, and serendipitously, Barnes just happened to reach out at the right time.

“I called other peanut places,” Barnes says, “But no one took me seriously until I met with the Hubbard family. They were so tickled to partner and put my peanuts in their lineup. It’s only been positive since then. It means the world to me.”

There is little doubt that Barnes will continue to succeed as he has decades of proof that he’s ambitious, diligent and dedicated. He calls back on his childhood and his parents for his character.

“There were many years growing up that there was no money because of elements surrounding sharecropping. We always came up a little bit short. But my father never gave up. He would come back that next year and plant and work all over again.

The thing I want to do is preserve some of the things that taught us how to be people, that taught us how to love, how to be honest, how to work, give, how to feel, how to have a great outlook on life. At the end of your life, you may never have achieved great riches, but it’s what will be said of you that matters. My father told me before he passed, ‘Son, I did the best I could with what I had to work with.’”

In terms of future plans, he says, “I intend to continue to do this as long as possible, then pass the farm to my son, who lives on the farm now and helps me. Then I have a grandson who’s interested. I’ve been talking to them about the history and legacy that’s behind all this and how important it is. I hope to keep the farm going for as long as possible. If they want to run it, everything is already set up. They just gotta put the labor in.”